Values (almost) don’t matter – but here’s the exception you can’t miss

You’ve probably heard it: “The stock market is expensive right now” or “Now is a good time to buy – the P/E ratio is low!” It sounds sensible. And yes, valuation is an important tool for long-term investors. But it’s not very useful if you’re trying to time the market in the short term.

It doesn't matter how low the valuation is – the market can still go down. And a high P/E ratio is no guarantee of an imminent decline. In the short term, the stock market is driven by other forces: expectations, interest rates, flows, macro, geopolitics – and not least by investor mood.

So the question is: How much does the valuation actually say about future returns? And on what time horizon Does it matter?

Market-level valuation: no help in 12 months

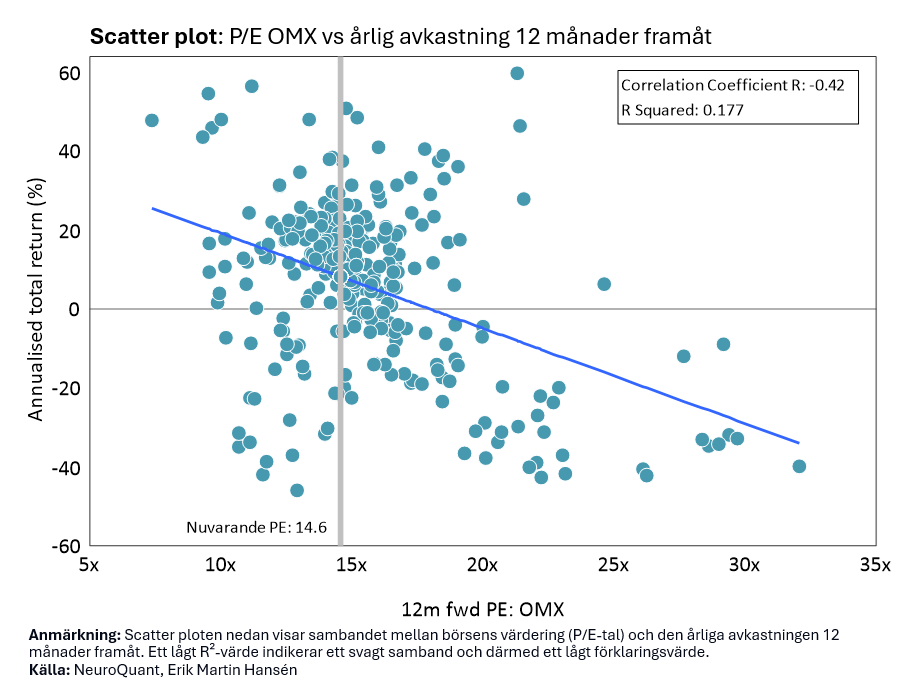

When we look at the valuation of, for example, OMXS30 – based on forward P/E ratios – and compare it to the future return one year later, the correlation is non-existent. The scatter plots look like a shower of confetti.

Why?

- The market is a complex system.

- In the short term, it is affected more by interest rates, inflation concerns, momentum flows and investor sentiment than by fundamentals.

- Multiples can both expand and contract without changing profits.

The result? You can buy “cheap” and lose money. You can buy “expensive” and have a fantastic year.

The scatter plot below shows the relationship between the stock market valuation (P/E ratio) and the annual return 12 months ahead. Each point represents a point in time: how expensive or cheap the market was – and how it fared since then. The spread is large. The market has sometimes given high returns despite high P/E ratios – and sometimes low returns despite low P/E ratios.

The R² value is 0.177, which means that only 17.7% of the variation in future returns can be explained by the P/E ratio. The rest – over 80% – is influenced by other factors: sentiment, interest rates, news feeds, psychology, etc.

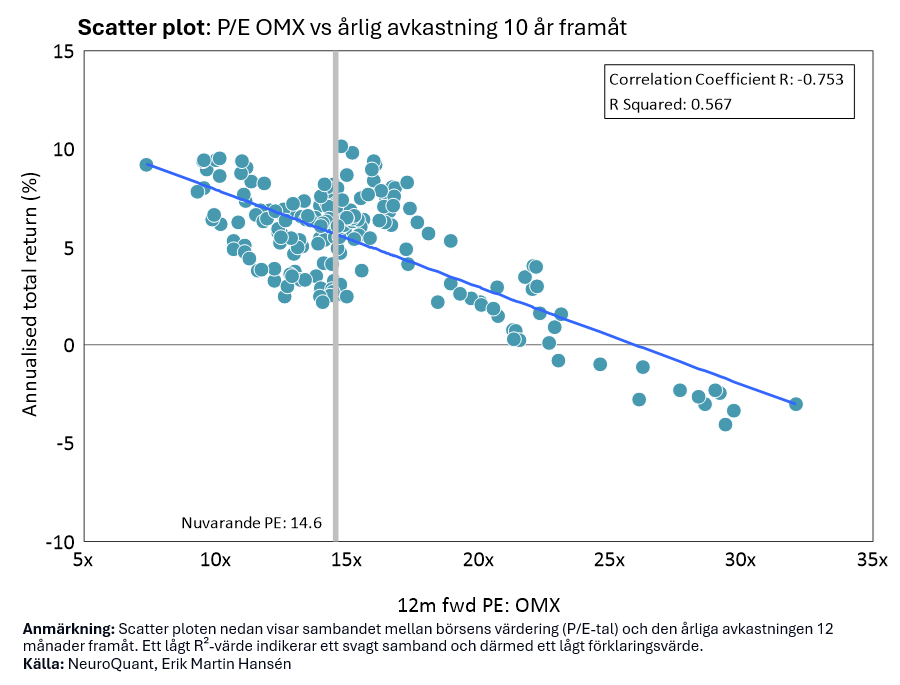

What does it look like in 10 years' time?

What does it look like in 10 years' time?

When we look at the relationship between the stock market valuation (P/E ratio) at a given time and the average annual return over the following 10 years, we see a clear pattern:

The higher the valuation, the lower the future return. 57% of the variation in future returns over 10 years can be explained by how over- or undervalued the market was at the start. This is a much stronger relationship than what we see in the short term, where R² is often close to zero.

But what about individual stocks?

Here it gets a little more nuanced. Individual stocks can sometimes react more quickly to valuation differences, but that requires the market to revalue the company – and that doesn't always happen.

Two common scenarios:

- Valuation doesn't matter in the short term here either. A company with a low P/E can remain undervalued for years unless sentiment changes. So-called value traps is more common than you think.

- But in some cases, valuation can play a role more quickly. If the company delivers stronger results than the market expects, there is a greater chance of a revaluation – especially in smaller companies where new information is disseminated more slowly.

In short: At the company level, valuation can sometimes provide better guidance, but only if you combine it with other factors such as: growth expectations, competitive advantages, management, profitability and cash flows.

It is not enough to simply compare the P/E ratio to the average.

So how should one think?

- At market level: Use valuation as a long-term tool – not as a timing tool.

- At company level: Valuation can be a piece of the puzzle, but it requires you to understand the bigger picture. A low valuation is no guarantee of an uplift – it could just as well be a warning sign.

Conclusion

Valuation is like a weather forecasting tool – it works best when you zoom out. If you look too close, it's just noise.

So the next time someone says “the market is overvalued” or “this stock is cheap,” ask a counter question:

On what time horizon?

Everything is decided there.